通过基于语料库的语言教学法(CBLP)提升高职英语教学与学习

本文旨在介绍基于语料库的语言教学法(CBLP)在高职英语教学与学习中的应用价值,并提供关于CBLP的教学建议。关于CBLP的实证研究介绍节选自Qing Ma, Jinlan Tang & Shanru Lin (2022)发表在《Computer Assisted Language Learning》期刊的文章《TESOL教师的基于语料库语言教学法的发展:通过在线协作促进的两步培训方法》,DOI: 10.1080/09588221.2021.1895225。在节选过程中,为了简明起见,部分表述进行了调整,但改编仍忠实于原文。

引言

研究表明,语料库语言学对语言研究和教师培训具有重要潜力,但大部分教师群体对其应用仍不熟悉(Boulton, 2017; Callies, 2019)。语料库素养(CL)是关键概念,指使用语料库技术进行语言研究并促进学生语言发展(Mukherjee, 2006; Heather & Helt, 2012)。此外,基于语料库的语言教学法(CBLP)强调将语料库技术融入课堂教学(Shulman, 1986, 1987)。本研究提出了一个两步框架,考察了TESOL学员在四周词汇课程中CL和CBLP的发展,旨在探索如何有效整合语料库资源于中小学课堂教学。

2. 研究问题

通过参与培训,教师培训学员在多大程度上能够发展他们的语料库素养(CL)?

教师培训学员在多大程度上能够发展他们的初步基于语料库的语言教学法(CBLP),即设计出令人满意的基于语料库的课程?

教师培训学员在多大程度上能够通过设计合适的基于语料库的教学材料来解决中国英语学习者的词汇困难/需求?

3. 研究方法

3.1 用于指导基于语料库教师培训的两步框架

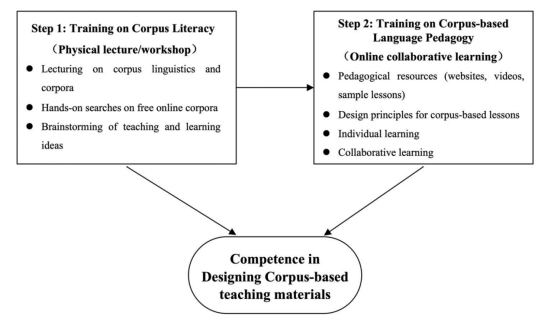

本文提出了一个两步框架来指导基于语料库的教师培训。由于语料库素养(CL)和基于语料库的语言教学法(CBLP)是两个不同的概念,培训可以分为两个步骤进行(见图1)。第一步主要通过课堂讲授和工作坊培养教师学员的初步CL,涉及语料库的基本概念、优势及实际操作。第二步则侧重于CL与CBLP的融合,通过在线平台进行个人和合作学习,帮助学员将语料库资源应用于课堂教学。整个过程结合了体验式学习、合作学习和社区学习的元素(Kolb, 1984; Vygotsky, 1978; Wenger, 1998),以促进学员间的互动和知识交换。

此外,研究团队设计的各种教学资源(如CAP平台和四步语料库教学设计模型)为学员提供了丰富的教学材料和思路,帮助他们在短时间内设计基于语料库的课程。这一培训框架通过螺旋式学习(Bruner, 1960),不断循环提高学员的教学设计能力。

图1. 提供基于语料库教师培训的两步框架(摘自原文)

3.2 CBLP发展的分析框架

本研究的一个重要目标是测量参与者的初步CBLP发展。为此,我们借鉴了Shulman(1987)的教学推理与行动模型。为支持他对内容知识和教学内容知识的区分,Shulman创建了该模型,以全面可视化教师教学内容知识发展的整个过程。该过程包括六个阶段:理解、转化、教学、评估、反思和新的理解,涵盖了教师设计、教学、评估和反思课程的关键阶段。由于我们所研究的对象是只需设计语料库课程而无需实际在课堂中实施的职前教师,因此前两个阶段——理解和转化——被视为本研究分析其课程计划的更合适的焦点。

4. 参与者与背景

本研究在香港一所大学的TESOL教师培训硕士项目中进行,共有33名学生参与,其中31名来自中国大陆或香港,2名来自北美,年龄在24至30岁之间。约三分之一的参与者有5个月至5年不等的教学经验。语料库培训项目嵌入了现有的英语词汇教学课程中。

5. 研究步骤

本研究的两步培训历时四周。第一步通过课堂讲解和示范,展示了语料库如何促进语言学习。学员们在Lextutor中搜索并纠正中国学习者常见的词汇错误,或完成填词练习,学习如何总结动词“insist”的用法模式。学员还通过小组合作,使用语料库资源设计教学方案,帮助学生区分容易混淆的词汇对(如形容词“interesting”和“interested”)。

第二步在线培训持续了三周。学员首先在CAP网站上学习语料库教学资源和课程设计原则。接着,观看视频教程学习COCA的关键搜索功能,并完成配对练习。最后一周,学员被分为八个小组,合作设计基于语料库的词汇课程,针对中国学习者在小学或中学英语学习中的常见词汇难点。在线学习通过Moodle平台进行,学员需上传小组作业,并在讨论区互相评论其他小组的设计,提供不少于100字的反馈意见。

6. 研究工具和数据收集

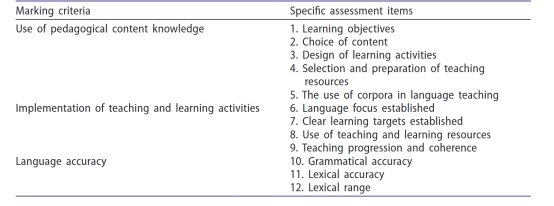

本研究采用混合研究方法,收集定量和定性数据,系统评估基于语料库的教师培训。首先,研究者设计了一份包含16个Likert量表题项和2个开放式问题的问卷,用于衡量参与者的语料库素养(CL)发展(Mukherjee, 2006)。问卷包含5个组件,Cronbach's α的信度分析显示各维度的信度高,范围为0.957至0.765。其次,研究者对8个基于语料库的词汇课程进行了评分,并通过内容分析评估参与者设计的课程。课程评分基于三个标准:教学内容知识的运用、教学活动的实施、语言准确性,评分采用五分制。最后,研究者通过半结构化访谈收集了参与者对培训的看法和自我反思,探讨他们的CL和CBLP发展。定性数据与定量数据结合使用,以回答三个研究问题,并追踪参与者CBLP发展的理解与转化阶段(Shulman, 1987)。

7. 研究结果

7.1通过参与培训,教师培训学员的语料库素养(CL)能够在多大程度上得到发展?

本研究探讨了教师培训学员在参与培训后其语料库素养(CL)的发展程度。通过Likert量表问题收集的数据显示,参与者普遍认为他们的CL有了良好的提升,平均得分大多在5分(满分6分)左右。其中,"对语料库数据的理解"得分最高(5.39),表明参与者对语料库及其数据的性质有了相当好的理解。其次是"语料库搜索技能"(5.24)、"使用语料库的优势"(5.00)和"语料库数据分析"(4.92)。最低得分项是"使用语料库的局限性"(4.76),表明该方面可通过进一步培训加强。访谈和开放式问题中的定性数据也支持了定量结果,特别是关于语料库为语言学习带来的优势。两大优势被特别强调:一是接触真实数据,二是学习搭配词的机会。

7.2教师培训学员在多大程度上能够发展他们的初步基于语料库的语言教学法(CBLP),即设计出令人满意的基于语料库的课程?

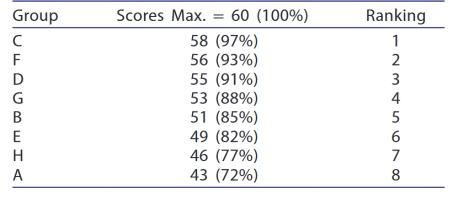

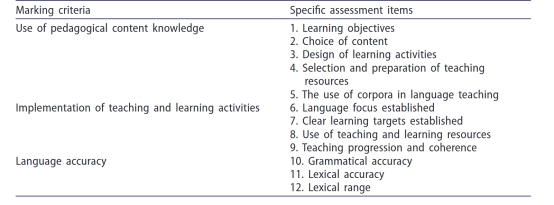

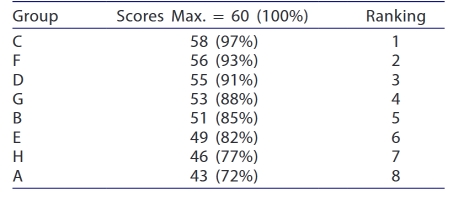

所有小组的基于语料库的词汇课程设计都根据表1的评分标准进行了定量评分,所有小组的得分均超过70%,其中六个小组的得分超过80%。评分结果显示,大多数学员在设计基于语料库的课程方面表现出了良好的能力。访谈和开放式问题的定性数据表明,参与者对他们的CBLP发展持积极态度。 通过数据分析,基于语料库的教学应用有四大优势被提炼出来:(1) 教授搭配词;(2) 提供真实语言示例;(3) 鼓励学生自主和归纳式学习;(4) 为教学活动设计提供资源(Shulman, 1987)。此外,学员们还提到了协作学习的好处,例如小组讨论和其他小组的反馈帮助他们改进课程设计。

表1. 课程设计的评分标准和评估项目 (摘自原文)

表1. 课程设计的评分标准和评估项目 (摘自原文)

7.3教师培训学员在多大程度上能够通过设计合适的基于语料库的教学材料来解决中国英语学习者的词汇难点/需求?

所有八个课程都进行了详细的内容分析,包括语言重点的选择、学习难点的性质以及教学活动的设计。研究发现,七个小组所选择的词汇对能够很好地解决中国英语学习者的需求和难点(表2),而教学活动普遍遵循了四步设计原则。这些步骤包括检测学生的词汇差距、引导学生通过语料库搜索观察语言模式、总结语言模式以及通过口头或书面练习巩固学习。

教学活动中还融入了非语料库的教学方式(如阅读故事、游戏等),并使用了多样的互动模式,如小组讨论和同伴合作,以增强学习兴趣和成效。参与者在课程设计中展示了对Shulman模型“转化”阶段的理解,通过语料库资源的使用和教师引导,将知识和技能有效传授给学生。

表2.课程设计的得分和排名 (摘自原文)

8. 讨论与启示

8.1在基于语料库的培训中为教师提供脚手架式支持

基于语料库的教师培训复杂,教师学员需要多种方式的支持。在教授学生之前,教师应逐步体验语料库搜索操作(Breyer, 2009;Johns, 1991;Mukherjee, 2004)。除了逐步的CL培训,教师还需要各种教学资源,如设计原则和示例课程的网站。小组合作能促进互动与知识交流,减少处理语料库数据的单调性(Leńko-Szymańska, 2014),并支持教师教学内容知识的发展(Shulman, 1987)。协作学习帮助学员发展CBLP,特别是在Shulman模型中的“理解”和“转化”阶段,提升了将语料库整合到课堂教学中的意识和实践。

8.2使用语料库资源教学以解决学生的词汇需求/难点

研究表明,语料库资源可以帮助解决中国英语学习者因语际和语内影响导致的词汇学习困难。例如,中文中的“孤独”对应英语的“alone”和“lonely”,“做”对应“make”和“do”,这些容易混淆的词对通过语料库的词汇搭配学习得以有效区分。同样,像“economic”和“economical”这样的同形异义词的学习困难也能通过语料库缓解。此外,语料库功能(如COCA的同义词搜索功能)有助于拓宽学生在写作中的词汇使用,这对于各类语言学习者都是有益的。进一步系统评估不同语料库网站的搜索功能,可以帮助教师更有效地将这些资源应用于教学(Mukherjee, 2004)。

8.3 在学校环境中实施有效的语料库教学时,教师可能需要考虑的因素

教师在实施基于语料库的教学时,应考虑以下因素:首先,教师应提供适当的指导,帮助学生逐步掌握语料库搜索技巧。Lin和Lee(2015)建议减少使用的语料库条目数量,完善并列句,并提出引导性问题。其次,课程设计应在语料库资源与其他教学活动之间取得平衡。基于语料库的活动能提供真实的语言示例并鼓励学生总结语言模式,但也应结合故事、游戏等活动以保持学生的兴趣。最后,课程设计应为学生创造足够的语言输出机会,如填空或交际练习,以巩固所学语言(Gass et al., 2013)。

9. 研究结论

本研究提出了语料库素养(CL)和基于语料库的语言教学法(CBLP)是两个不同的概念。前者侧重于学习语料库语言学,包括搜索和分析技能,而后者则是在课堂教学中应用前者的能力,类似于Shulman(1986, 1987)提出的教学内容知识。基于这一区别,研究引入了一个两步框架用于语料库教师培训,并对一组TESOL学员进行了培训,结果显示大多数参与者在CL的关键维度上表现出较高的自我评价,并且他们充分认识到使用语料库的优势,如提供真实语言数据和学习搭配词。课程设计评估表明,大多数小组能够设计出适当的基于语料库的课程,展现了将语料库资源融入课堂教学的良好教学意识。尤其是在“理解”和“转化”阶段,学员的教学内容知识(CBLP)得到了充分发展(Shulman, 1987)。研究证明了将CL和CBLP作为两个独立概念有助于推动语料库教师培训。未来研究应进一步探索教师在整合语料库资源进入课堂教学时所需的知识维度。

10. CBLP在高职英语教学与学习中的应用价值

基于语料库的语言教学法(CBLP)与高职英语教学与学习密切相关,尤其是在培养《高等职业教育专科英语课程标准(2021年版)》所强调的学科核心素养方面。该课程标准明确指出,发展学生的核心素养是高职英语课程的主要目标,包括职场涉外沟通、多元文化交流、语言思维提升,以及自主学习完善。CBLP通过将语料库语言学与外语教学法相结合,构建适合学生个性化学习和自主学习的教学模式。这种方法不仅能够提升学生对语言规则的掌握,还能够增强他们的职场沟通能力、跨文化交流能力、语言思维能力和自主学习能力,与高职英语教学培养学科核心素养的目标高度一致。CBLP契合高职学生的学习需求,因为它强调在真实情境中应用语言的能力。通过数据驱动的语言学习模式,CBLP鼓励学生通过自主学习、合作学习和探究式学习深入理解语言的内在规律,促进学生的全面发展和个性化发展。综上所述,CBLP顺应了信息化背景下教与学方式的变革,帮助教师充分利用语言大数据,更有效地应对教学中的挑战,并提升高职英语教学的整体质量。

11. CBLP的国际国内应用现状

CBLP的提出者马清博士及其团队通过深入研究,强调了该方法在促进英语作为外语/第二语言教师专业成长方面的显著作用。来自100多个国家和地区的6000多名教师报告了技术技能、教学方法和教学自信的提升,以及对学生学习成果的改善。

12.CBLP的教学建议和资源支持

CBLP通过创建在线协作学习环境,支持教师持续的专业发展。该协作平台促进了教师间的交流、知识共享,并构建了一个致力于专业成长的国际教师社区。为了更好地服务于教师的教学需求,平台提供了以下支持方式:

资源获取:为英语教师提供通过CBLP研究开发的开放获取的资源包。这些资源包包括全面的指导、培训材料和创新的教学策略。

研讨培训:提供专门的研讨会和培训课程,让教师熟悉CBLP的原则、技术和工具。鼓励积极参与、反思和实践操作。

逐步整合:支持英语教师逐步将CBLP整合到他们当前的教学实践中。提供持续的指导,确保平稳过渡,并帮助教师充分利用CBLP来提高学生的参与度和促进语言能力的提升。

交流平台:为教师提供分享经验、交流最佳实践的平台和参与协作CBLP相关研究的机会。组织研讨会、会议或在线论坛,以培养一种持续改进和专业发展的氛围。

13. 总结

基于CBLP的教学方法通过提供真实的语言数据和工具,能够为学生创造更加有意义的英语学习体验,帮助他们发现语言的内在规律。该方法不仅有助于学生的语言应用能力提升,还能有效促进其核心素养的发展。通过这种方式,高职英语教师可以更好地激发学生的学习积极性和主动性,教会学生如何独立学习和探索问题,培养终身学习习惯,推动学习可持续发展。

Enhancing English Teaching and Learning in Higher Vocational Education through Corpus-Based Language Pedagogy (CBLP)

This article aims to introduce the practical value of Corpus-Based Language Pedagogy (CBLP) in English language teaching and learning in higher vocational education, and to provide pedagogical recommendations related to CBLP. The excerpted empirical research on CBLP is drawn from the article The Development of TESOL Teachers’ Corpus-Based Language Pedagogy: A Two-Step Training Approach Facilitated by Online Collaboration, authored by Qing Ma, Jinlan Tang & Shanru Lin (2022) and published in the journal Computer Assisted Language Learning, DOI: 10.1080/09588221.2021.1895225. For brevity, some expressions have been modified, but the adaptation remains faithful to the original article.

Introduction

Research shows that corpus linguistics holds significant potential for language studies and teacher training, yet remains unfamiliar to most educators (Boulton, 2017; Callies, 2019). Corpus literacy (CL) refers to the ability to use corpus tools for language investigation and student development (Mukherjee, 2006; Heather & Helt, 2012). Corpus-based language pedagogy (CBLP), akin to Shulman’s pedagogical content knowledge, focuses on integrating corpus tools into classroom teaching (Shulman, 1986, 1987). This study introduces a two-step framework to explore the development of CL and CBLP among TESOL trainees during a four-week vocabulary course, aiming to find effective ways to integrate corpus resources into primary and secondary education.

Research questions

The present study aims to address the following research questions:

To what extent can teacher trainees develop their CL by participating in the training?

To what extent can teacher trainees develop their initial CBLP, i.e. satisfactory corpus-based lessons?

To what extent can teacher trainees address the vocabulary difficulties/needs of Chinese English learners by designing appropriate corpus-based teaching materials?

Research method

A two-step framework for guiding corpus-based teacher training

This paper proposes a two-step framework to guide corpus-based teacher training. Since corpus literacy (CL) and corpus-based language pedagogy (CBLP) are two distinct concepts, the training is divided into two steps (see Figure 1). The first step focuses on developing the teacher trainees' initial CL through classroom lectures and workshops, which cover the basic concepts, advantages, and practical operations of corpora. The second step emphasizes the integration of CL and CBLP, engaging the participants in individual and collaborative learning through an online platform. This helps them apply corpus resources to classroom teaching. The entire training process integrates elements of experiential learning, collaborative learning, and community learning (Kolb, 1984; Vygotsky, 1978; Wenger, 1998), promoting interaction and knowledge exchange among the participants.

In addition, the research team has designed various pedagogical resources, such as the CAP platform and a four-step corpus-based lesson design model, providing the participants with rich materials and ideas to help them design corpus-based lessons in a short time. This framework follows the idea of spiral learning (Bruner, 1960), allowing participants to continuously improve their teaching design abilities through iterative learning.

Figure 1. A two-step framework for providing corpus-based teacher training (Reproduced from the original journal article)

Analytical framework of CBLP development

One important goal of the current study is to measure participants’ initial CBLP development. We borrowed Shulman’s (1987) model of pedagogical reasoning and action for this purpose. In support of his differentiation between content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge, Shulman created this model to provide a holistic visualisation of the entire process of how teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge is developed. This process comprises six stages: comprehension, transformation, instruction, evaluation, reflection and new comprehensions, all of which can capture the essential stages where the teacher designs, teaches, evaluates and reflects upon a lesson. Because we involved preservice teachers who only needed to design corpus lessons without actually implementing the lessons in classrooms, the first two stages – comprehension and transformation – were deemed more suitable as the focus of the study in analysing their lesson plans.

Participants and context

The present study was conducted at a university in Hong Kong as part of an MA programme for training TESOL teachers. A total of 33 students participated in the study, of whom 31 were of Chinese origin, either from mainland China or Hong Kong, and two were from North America. The participants were aged between 24 and 30. About one-third of the participants had teaching experience, ranging from five months to five years. The corpus-based training programme was integrated into an existing vocabulary course for English language teaching.

Research procedure

The two-step training in this study lasted four weeks. In the first step, lectures and demonstrations were used to showcase how corpora can facilitate language learning. The participants searched in Lextutor to correct common lexical errors made by Chinese learners or completed gap-filling exercises, learning how to summarize the usage patterns of the verb “insist”. They also collaborated in small groups, using corpus resources to design teaching plans to help students distinguish between easily confused lexical pairs (such as the adjectives “interesting” and “interested”).

The second step of the online training lasted three weeks. First, participants studied corpus-based pedagogical resources and lesson design principles on the CAP website. They then watched video tutorials to learn key search functions on COCA and completed matching exercises. In the final week, participants were divided into eight groups and collaborated to design corpus-based vocabulary lessons targeting common difficulties faced by Chinese learners in primary and secondary schools. The online learning was conducted through the Moodle platform, where students uploaded their group work, provided feedback on at least two other groups' lesson designs, and engaged in peer discussion, giving feedback of at least 100 words per comment.

Research instruments and data collection

This study employed a mixed methods design to systematically evaluate corpus-based teacher training by collecting both quantitative and qualitative data. First, the researchers developed a 16-item Likert-scale survey along with two open-ended questions to assess participants’ development of corpus literacy (CL) (Mukherjee, 2006). The survey contained five components, and a Cronbach’s α reliability analysis showed high reliability for each dimension, ranging from 0.957 to 0.765.

Second, the researchers evaluated eight corpus-based vocabulary lessons designed by participants using three criteria: (1) use of pedagogical content knowledge, (2) implementation of teaching and learning activities, and (3) language accuracy. The lessons were rated on a five-point scale, and inter-rater reliability reached 85%.

Lastly, semi-structured interviews were conducted to gather participants’ reflections on the training and their development in CL and corpus-based language pedagogy (CBLP). The qualitative data from interviews and open-ended questions were combined with the quantitative findings to address the study's research questions and to track participants’ CBLP development, linking it to Shulman’s (1987) comprehension and transformation stages.

7. Research results

7.1 To what extent can teacher trainees develop their CL by participating in the training?

This study examined the extent to which teacher trainees developed their corpus literacy (CL) after participating in the training. Data collected from the Likert-scale questions showed that participants generally perceived an improvement in their CL, with average scores around 5 out of 6. The highest score was for “understanding of corpus data” (5.39), indicating that participants gained a solid understanding of what a corpus is and how to work with corpus data. This was followed by “corpus search skills” (5.24), “advantages of using corpora” (5.00), and “corpus data analysis” (4.92). The lowest score was for “limitations of using corpora” (4.76), suggesting that this area could benefit from further training.

Qualitative data from interviews and open-ended questions supported the quantitative results, particularly highlighting two main advantages of corpora: access to authentic data and the opportunity to learn collocations.

7.2 To what extent can teacher trainees develop their initial CBLP, i.e. satisfactory corpus-based lessons?

All group corpus-based vocabulary lessons were quantitatively rated according to the criteria in Table 1. All groups scored above 70%, with six groups achieving over 80%. The results indicate that most participants demonstrated a good ability to design corpus-based lessons. Qualitative data from interviews and open-ended questions also showed that participants had a positive attitude toward their CBLP development.

Four major advantages of corpus-based teaching applications were identified from the data analysis: (1) teaching collocations, (2) providing authentic language examples, (3) encouraging student independence and inductive learning, and (4) offering resources for designing teaching activities (Shulman, 1987). Additionally, participants mentioned the benefits of collaborative learning, such as group discussions and feedback from other groups, which helped them improve their lesson designs.

Table 1. Marking criteria and assessment items for lesson design

(Reproduced from the original journal article)

(Reproduced from the original journal article)

7.3 To what extent can teacher trainees address the vocabulary difficulties/ needs of Chinese English learners by designing appropriate corpus-based teaching materials?

All eight lessons underwent a detailed content analysis, examining the choice of language focus, nature of learning difficulties, and the design of teaching activities. It was found that seven out of eight groups selected appropriate word pairs that effectively addressed the needs and difficulties of Chinese English learners (Table 2). Most of the teaching activities followed the four-step design principles, including identifying lexical gaps, guiding students through corpus searches, summarizing language patterns, and practicing through oral or written exercises.

Non-corpus-based teaching activities (e.g., story reading, games) were also incorporated, and varied interaction modes like group work and discussions were used to enhance student engagement and learning outcomes. Participants demonstrated their understanding of Shulman’s “transformation” stage by effectively using corpus resources and teacher guidance to transmit knowledge and skills to their students.

Table 2. The score and ranking of lesson design

(Reproduced from the original journal article)

8. Discussion and implications

8.1 Scaffolding teachers in corpus-based training

Corpus-based teacher training is complex, and teacher trainees need support in various ways. Before teaching students, teachers should first undergo step-by-step hands-on corpus search training (Breyer, 2009; Johns, 1991; Mukherjee, 2004). In addition to step-by-step CL training, teachers also require pedagogical resources, such as websites that offer design principles and sample lessons. Group collaboration fosters interaction and knowledge exchange, reducing the monotony of working with corpus data (Leńko-Szymańska, 2014) and supports the development of teachers' pedagogical content knowledge (Shulman, 1987). Collaborative learning aids in the development of CBLP, particularly in the ‘comprehension’ and ‘transformation’ stages of Shulman’s model, enhancing teachers' awareness and practical skills in integrating corpus tools into classroom teaching.

8.2 Teaching students with corpus resources to address their vocabulary needs/difficulties

Research shows that corpus resources can help address vocabulary learning difficulties faced by Chinese learners of English due to both interlingual and intralingual influences. For example, the Chinese word “孤独” corresponds to both “alone” and “lonely” in English, and “做” corresponds to both “make” and “do”, which often leads to confusion. Corpus-based collocation learning can effectively help students differentiate these easily confused lexical pairs. Similarly, learning difficulties with synforms, such as “economic” and “economical,” can also be alleviated using corpus data.

Furthermore, corpus functions like the synonym search in COCA can help expand students’ vocabulary use in writing, which benefits learners from various linguistic backgrounds. A systematic evaluation of the different search functions on corpus websites could further aid teachers in integrating these tools into their teaching (Mukherjee, 2004).

8.3 Factors teachers may consider in implementing effective corpus-based teaching in school settings

When implementing corpus-based teaching, teachers should consider the following factors: First, they should provide appropriate guidance to help students gradually master corpus search techniques. Lin and Lee (2015) recommend reducing the number of corpus entries, using complete concordance lines, and posing guiding questions. Second, lesson design should balance the use of corpus resources with other activities. While corpus-based activities offer authentic language examples and encourage students to summarize language patterns, incorporating stories, games, and other activities can help maintain student interest. Lastly, lessons should provide ample opportunities for language output, such as gap-filling or communicative practice, to consolidate what students have learned (Gass et al., 2013).

9. Research conclusion

This study distinguishes between corpus literacy (CL) and corpus-based language pedagogy (CBLP) as two distinct concepts. CL focuses on the learning of corpus linguistics, such as search and analysis skills, while CBLP involves applying these skills in classroom teaching, akin to Shulman’s (1986, 1987) pedagogical content knowledge. A two-step framework for corpus-based teacher training was introduced, and TESOL trainees were trained. Results show that most participants rated themselves highly in key CL dimensions and recognized the benefits of corpora, such as providing authentic language data and learning collocations. Lesson evaluations revealed good pedagogical awareness of integrating corpus resources into teaching, especially in the stages of “comprehension” and “transformation” (Shulman, 1987). The study confirms that distinguishing CL and CBLP aids in promoting corpus-based teacher training. Further research is needed to explore the knowledge dimensions required for integrating corpus resources into classroom teaching.

10. The practical value of CBLP in higher vocational English teaching and learning

CBLP is closely related to English teaching and learning in higher vocational education, especially in fostering the core competencies emphasized in the Higher Vocational Education English Curriculum Standards (2021 Edition). These standards explicitly state that the main goal of English courses for higher vocational education is to develop students’ core competencies, including workplace communication in foreign languages, cross-cultural exchange, language reasoning skills, and autonomous learning. CBLP integrates corpus linguistics with foreign language pedagogy to create a teaching model that supports personalized learning and autonomous learning for students. This method not only enhances students’ mastery of language rules but also strengthens their workplace communication, cross-cultural communication, language reasoning, and autonomous learning skills, which align perfectly with the objectives of fostering core competencies in higher vocational English education. CBLP meets the learning needs of vocational students because it emphasizes the ability to apply language in real-world contexts. Through a data-driven language learning model, CBLP encourages students to deeply understand the inherent patterns of language through autonomous, collaborative, and inquiry-based learning, promoting both holistic and personalized development. In conclusion, CBLP aligns with the transformation of teaching and learning methods in the context of digitalization, helping teachers make full use of big data, effectively addressing challenges in language teaching and learning, and improving the overall quality of higher vocational English education.

11. The current international and domestic applications of CBLP

Dr. Qing Ma, the creator of CBLP, along with her research team, has conducted in-depth studies emphasizing the significant role of this approach in promoting the professional growth of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) and English as a Second Language (ESL) teachers. Over 6,000 teachers from more than 100 countries and regions reported improvements in their technological skills, pedagogical methods, and teaching confidence, as well as improvements in their students’ learning outcomes. CBLP represents a specific application of corpus technology within the framework of Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK), effectively integrating corpus linguistics and language pedagogy.

12. CBLP teaching recommendations and resource support

CBLP supports ongoing professional development by creating an online collaborative learning environment. This platform fosters communication among teachers, facilitates knowledge sharing, and builds an international community of educators committed to professional growth. To better meet the teaching needs of educators, the platform offers the following support mechanisms:

Resource Access: Provide English teachers with open-access resource packages developed through CBLP research. These packages include comprehensive guidance, training materials, and innovative teaching strategies.

Workshops and Training: Offer specialized workshops and training sessions to familiarize teachers with CBLP principles, techniques, and tools. Encourage active participation, reflection, and practical implementation.

Gradual Integration: Support English teachers in gradually integrating CBLP into their current practices. Provide ongoing mentorship to ensure a smooth transition and help teachers fully leverage CBLP for student engagement and language acquisition.

Networking Opportunities: Facilitate opportunities for teachers to share experiences, best practices, and engage in collaborative CBLP-related research. Organize seminars, conferences, or online forums to foster a culture of continuous improvement and professional growth.

13. Conclusion

CBLP, through authentic language data and tools, creates more meaningful English learning experiences for students, helping them uncover the inherent patterns of the language. This pedagogical model not only enhances students’ language application skills but also effectively promotes the development of their core competencies. In this way, English teachers in higher vocational education can better motivate students, foster independent learning and problem-solving skills, cultivate lifelong learning habits, and support sustainable learning development.

References

Boulton, A. (2017). Corpora in language teaching and learning. Language Teaching, 50(4), 483–506. doi:10.1017/S0261444817000167

Breyer, Y. (2009). Learning and teaching with corpora: Reflections by student teachers. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 22(2), 153–172. doi:10.1080/09588220902778328

Bruner, J. S. (1960). The process of education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Callies, M. (2019). Integrating corpus literacy into language teacher education. Learner Corpora and Language Teaching, 92, 245.

Gass, S., Behney, J., & Plonsky, L. (2013). Second language acquisition. New York: Routledge.

Heather, J., & Helt, M. (2012). Evaluating corpus literacy training for pre-service language teachers: Six case studies. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 20(4), 415–440.

Johns, T. (1991). From printout to handout: Grammar and vocabulary teaching in the context of data-driven learning. English Language Research Journal, 4, 27–45.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Leńko-Szymańska, A. (2014). Is this enough? A qualitative evaluation of the effectiveness of a teacher-training course on the use of corpora in language education. ReCALL, 26(2), 260–278. doi:10.1017/S095834401400010X

Lin, M. H., & Lee, J. Y. (2015). Data-driven learning: Changing the teaching of grammar in EFL classes. ELT Journal, 69(3), 264–274. doi:10.1093/elt/ccv010

Ma, Q., & Lee, H. T, Gao, X., Chai, C.-S. (2024). Learning by Design: Enhancing Online Collaboration in Developing Pre-Service TESOL Teachers’ TPACK for Teaching with Corpus Technology. British Journal of Educational Technology.

Ma, Q., Yuan, R., Cheung, L. M. E., & Yang, J. (2024). Teacher paths for developing corpus-based language pedagogy: A case study. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 37(3), 461-492.

Ma, Q., Chiu, M.M., Lin, S., & Mendoza, N. B. (2023). Teachers’ perceived corpus literacy and their intention to integrate corpora into classroom teaching: A survey study. ReCALL, 35(1), 19-39.

Ma, Q., Tang, J., & Lin, S. (2022). The development of corpus-based language pedagogy for TESOL teachers: A two-step training approach facilitated by online collaboration. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35 (9), 2731-2760.

Mukherjee, J. (2004). Bridging the gap between applied corpus linguistics and the reality of English language teaching in Germany. In U. Connor & T. Upton (Eds.), Applied corpus linguistics: A multidimensional perspective (pp. 239–250). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Rodopi.

Mukherjee, J. (2006). Corpus linguistics and language pedagogy: The state of the art and beyond. In S. Braun, K. Kohn, & J. Mukherjee (Eds.), Corpus technology and language pedagogy: New resources, new tools, new methods. (pp. 5–24). Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Peter Lang.

Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–14. doi:10.3102/0013189X015002004

Shulman, L. S. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1–22. doi:10.17763/haer.57.1.j463w79r56455411

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.